Never had I even left Europe before. But there I was descending down the rickety plane steps, running on less than two hours of abysmal sleep. My heart raced with both fear and hesitation as I was about to meet the strangers with whom I would be sharing my next few weeks.

Bali: No go or slow?

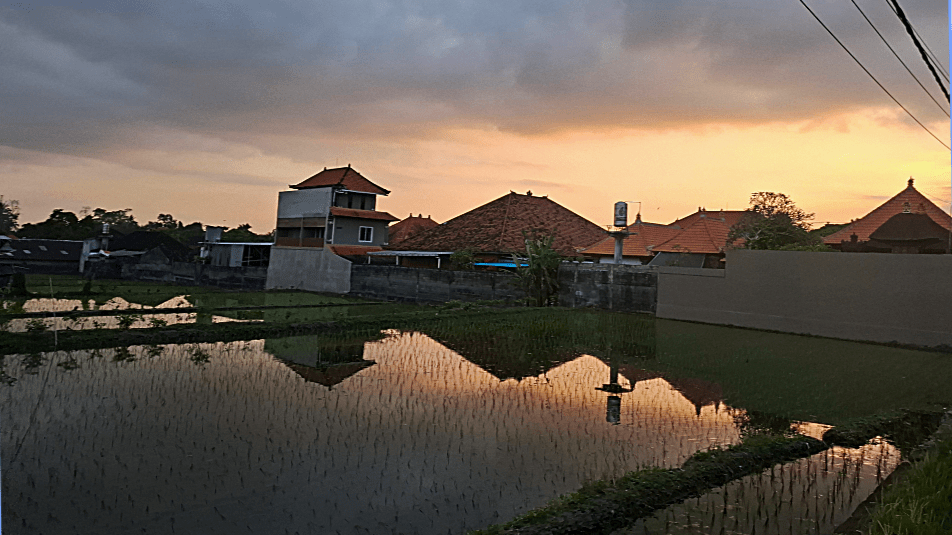

As the car trundled along, I was filled with childish awe and the uncertainty that embodies your early 20s. Bali appeared somewhat different from either of the narratives I had previously painted. It was far from the obnoxious, litter-filled, party island that I had been scaremongered into believing. Instead, as my head rested against the car window, I caught local craftspeople perched on the pavement. Whilst flowers littered the streets, and I occasionally got a glance of thin strips of rice fields meandering into the distance.

But sadly, I didn’t feel like I was going to enter a painting. Rolling the window down a tiny notch exposed me to the grumble of countless motorcycles, accompanied by the poignant fumes. Meanwhile, thick, hot rain angrily splattered through, trickling down my already messed-up skin.

First impressions count. I had not landed in paradise. But I couldn’t help wondering what waited inside each inquisitive temple, what stories were hidden behind each friendly face, and what lay beyond the broad horizons.

The more time I spent in Bali, the more their narrative unfolded. Contrast the serenity of remote areas with the tumultuous roars of their busy capital. A place can never be perfect. But I am even more thankful for the ample opportunities we had to step back and connect with the community.

Are the locals practising slow living without knowing it?

People hugely influence a place. We were warmly welcomed, and many were eager to share their knowledge and stories. At first, I couldn’t help but notice how happy they appeared. Which was a question that I kept returning to. As scorching heat swept across my face, it became increasingly clear that locals possessed much less than we did. That could be why extended families shared cooking spaces, why most never left Indonesia, and why simple activities appeared to be enough.

How about when we had to slow down?

There were ample times when we had no option but to pause. Long evenings without alcohol meant we needed to revert to cards as a form of entertainment. Slow mornings allowed me to hear the laughter of enthusiastic schoolchildren as I gazed out across the balcony, breathing in the fresh, tropical air. Ironically, though, the most significant factor was the traffic.

I was accustomed to having something to focus on immediately when I woke up, so spending an hour just in my room felt both irritating and challenging. I felt lazy, even restless.

But after adjusting, this ‘new lifestyle’ became incredibly enjoyable. Who wouldn’t want to spend their mornings learning, afternoons exploring, and still very warm evenings gathered around the outside dinner table? To experience all a place has to offer, with plenty of time to relax, is an immense privilege, one that is simply inaccessible to many.

The only aspect of the ‘slow life’ that I never warmed to was the traffic. It was boring, hot, and I felt car sick. Goodness knows how the locals felt. The traffic situation is very multifaceted, although I am sure that Bali’s influx of tourists and expats has contributed.

Stuck in the turbulence of traffic:

There was little to do whilst cooped up in the car. So I let my eyes wander to whatever was happening outside. My mind drifted in circles, trying to fill the missing roundabout void. During my aimless gazing, I kept catching workers patching the holes in pavements, probably so tourists could walk across at ease. There was very little in the way of personal protective equipment, and I certainly didn’t assume that these people were happy. One of my friends later commented on how many had yellow eyes, which is a sign of poor health. We can look at some and admire the positive aspects of their lives that they kindly share with us. Yet, someone’s happy moments never provide a complete picture.

If the city centre was harsh, Nusa Penida was harsher. We felt our bones being shaken as the van patiently trundled along the roads. Each time it swerved, I caught little glimpses. Either of basic shacks or of vapid villas proudly posed amidst untouched hills and landscapes. When we finally arrived at paradise’s top paradise, endless hot influencers lined up against the genuinely attractive coastline. Why was such a picture-perfect place being turned into a performance? Led by the wealthy for the wealthy, fuelled by the tourism industry. I’d seen that much of Bali wasn’t like that. Witnessing this drastic divergence at the expense of people was disconcerting.

But when hideous meets hideous, enough becomes enough. The development of an elevator to the beach was reversed due to multiple violations. I had noticed many tourists and travellers express discontent. And part of this might be because we value taking time to appreciate the beauty of places and people.

So why should we slow down?

It helps us appreciate the little things, consider our perspectives before they become narratives, and enables us to connect with ourselves and others more effectively. All vital for our own wellbeing, other people’s, and the planet’s. I can be prone to jumping to conclusions, forgetting to show kindness, and failing to consider everyone’s perspectives because they are unknown to me. Pausing for myself and others enables me to think more deeply about how my actions and external events impact them.

What about when the same happens structurally? In many cases, a handful benefit financially at the expense of a few. Most aren’t considered, and the long-term risks are shamefully overlooked. I couldn’t help but compare my experiences engaging in locally run initiatives and my less pleasant encounters elsewhere. I feel honoured to have been part of what the Balinese people loved. Slowing down may at least enable you to spot when something is up, such as that ugly elevator. It also provides sufficient time to reflect on what is occurring, enabling you to engage in activities that are likely to be more beneficial for those who you are surrounded with.

Some overdeveloped areas felt superfluous. People engaged with us, most likely because that was the only way they could make a living. Remembering how many were forced to pave the streets for tourists helped me to understand the why. In these places, what did the locals have left?

So what’s good about living slowly?

Slow travel to me encapsulates an umbrella. I used to think it was mainly about spending more time in one location. Although this is impossible for many travellers. What if they can only take a week off work, or if they need to return to care for their family? Instead, I’d say it also includes keeping your eyes open, letting your thoughts wander, and asking lots of questions.

It sounds simple, but rather than focusing on media-curtailed assumptions, I can consider how various actions, occurrences, and developments impact others. So many love discussing their own and their country’s history, so what good would another mammoth elevator do?

If you’re not travelling, then I still think you should take note. Slowing down does not entail spending half your days ‘bedrotting’, choosing not to have something to focus on, or living ‘the soft life’. Instead, it is allowing time to recharge, notice things, and make time for others. It feels refreshing, helps clear your mind, and can enable more balanced decisions. Those who can should take that time, not only for themselves, but to notice how their choices impact others, for better or worse. Not everyone has the time. But many voices are marginalised.

What experiences have you had when you have taken even small actions to ‘slow down’? And how would you define slow travel? I would be interested in knowing this in the comments.

Leave a comment